The Pappas Restaurants family-run empire includes everything from coffee shops to upscale steakhouses, from Arizona to Georgia and Texas to Illinois. But its home — and perhaps its most loyal customers — are in Houston, where its roots can be traced to a restaurant supply and equipment company that began in 1945.

Though the company’s unsuccessful battle to retain its contract to sell food at William P. Hobby Airport has focused public attention on the locations lining the terminals at the city’s small airport, Pappas has more than 50 restaurants across the Houston area, from downtown to distant suburbs. Because the company is privately held, its financial information is closely guarded, with outside estimates varying widely.

Every corner, every cuisine

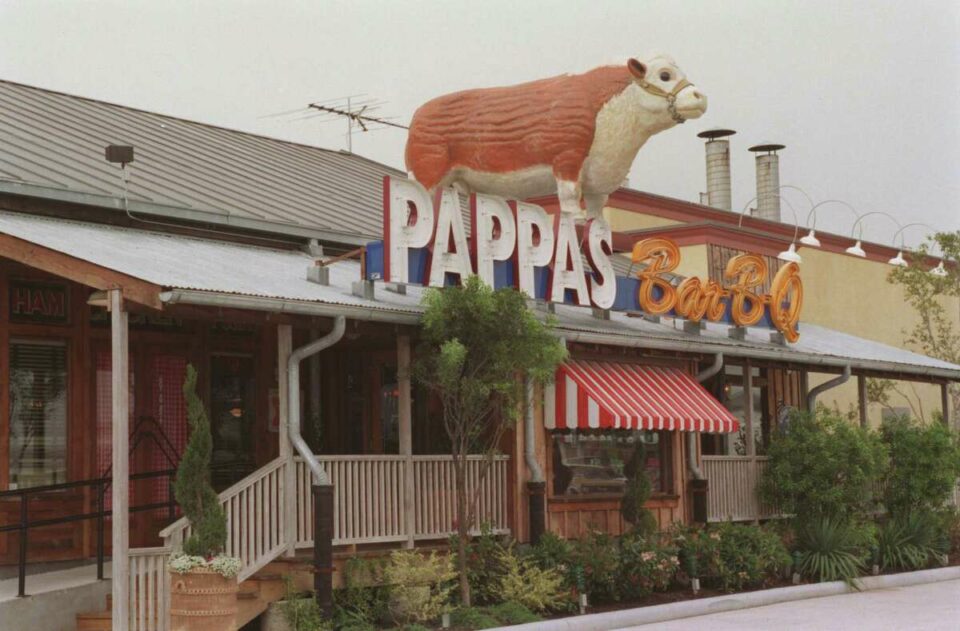

The first restaurants bearing the family’s name were started in 1897 by H.D. Pappas, but his four sons started the chain most locals know in 1966 when the Dot Coffee Shop opened in south Houston. A year later Pappas Brisket House downtown, now known as Pappas Bar-B-Q, followed, according to the company.

From there, two more generations of the family have helped build the brand to nine restaurant concepts, from coffee to seafood to burgers. Their success across the various cuisines comes down to good instincts about what consumers want, where they want it and where Pappas can add value, says Christina Pappas, the restaurant group’s director of marketing.

“There’s an idea that everything we touch turns to gold,” said Pappas Chief Operating Officer Mike Rizzo. “Well, it’s a lot of work turning things into gold.”

But the work is made easier by the company’s tight control of distribution, purchasing, warehouses and more for all nine restaurant concepts, allowing them to buy in bulk, she said. Shrimp, for example, is caught on the same boat and delivered by the same truck, no matter whether it’s getting turned into a shrimp taco at Pappasito’s Cantina or a gumbo at Pappadeaux Seafood Kitchen, Rizzo said.

The restaurant group also employs a group of “concept leaders” that operate each restaurant style and share best practices and new ideas with each other, he said.

The integration, Rizzo said, helps the family maintain the same quality experience at each restaurant.

Recent reopenings

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, most of Pappas’s restaurants have continued to perform well, the result of strong customer loyalty and the chain’s reputation for being clean and well-run, he said. But early in the COVID outbreak, the company took a close look at each restaurant and saw an opportunity to re-purpose some of its real estate.

Ultimately, five Houston Pappas locations were closed in 2020 and employees at those sites were moved to other local restaurants.

“It’s not that those five restaurants couldn’t provide, it was just an opportunity to do better on the heels of the pandemic and the uncertainty,” Rizzo said.

Closing the restaurants was the first step in a process that helped Pappas reshuffle some of its lineup. Last year, it began the second step, rebranding the closed Yia Yia Mary’s Mediterranean Kitchen into Yia Yia Pappas on the site of what used to be a Pappadeaux. This spring, the company will open Little’s Oyster Bar at the site of a closed Little Pappas Seafood on South Shepherd Drive and West Alabama Street.

The airports

Losing the contract to serve food at Hobby may prove to be the most notable change in the Pappas lineup. But air travelers will still be able to grab some Pappadeaux seafood in George Bush Intercontinental Airport, which the company has served since 2003, and at Dallas/Fort Worth International, a Pappas outpost since 2010.

Rizzo — who oversaw Pappas’s airport operations for more than a decade — admits it’s a challenge to put a restaurant in an airport while maintaining the quality of a standalone operation.

Because there’s far less space, Pappas uses an outside kitchen to prepare food before delivering it to the airport each day, he said. Pappas’s designers also had to experiment with ways to adapt the brand’s signature building design to its airport locations.

Less space also means fewer seats for customers. But because flights arrive and depart throughout the day, those seats are constantly filled, Rizzo said. Overall, the airport locations are about as profitable as the company’s standalone restaurants. There’s just “a different path to get there,” he said.

The success Pappas had in recreating its experience and quality in an airport, Christina Pappas said, could be seen in the way customers continued to show their loyalty to the brand.

“You’ll see people making a point to come early and dine with us because they will enjoy the meal and because it is so similar to the street-type location. You’ll see people on the way home picking up dinner for their family,” she said. “We are special in that regard.”

And while the loss of the Hobby contract is a blow to the company, it doesn’t reduce the company’s vast footprint across its home turf, where diners still enjoy a family-run restaurant — without paying to park or removing their belts and shoes.